Mech Dara and Erin Handley

The Phnom Penh Post, Fri, 11 November 2016

Tracing the space between the tiles on the table with her fingertip, Thavery* recalls how her teacher locked her in his classroom and stripped off her shirt and skirt.

She has been forced to tell this story time and again, in front of courts, police and NGO workers, unearthing scenes she’d rather forget. It could re-traumatise her, but despite this, she tucks a lock of red-tinged hair behind her ear and agrees to speak, again.

It was May 2013, and she was 14 years old. Her Grade-Six classmates were on a field trip; Thavery had been forced to stay behind.

Her teacher, Kem Chan Chhen, grabbed her breasts and forced his mouth on hers, she says. It wasn’t the first time, but it was the worst.

“I was shaking, and I asked why he did that. He said he loved me and that’s why he played with me like this,” Thavery says. “I was scared.”

She believes she would have been raped if her classmates hadn’t suddenly returned.

But Thavery was not the only girl he allegedly preyed upon. Three others later came forward with claims of sexual assault. None of them had breathed a word, despite that the teacher had allegedly groped them during class, in plain view of the rest of the students.

He threatened them. They would not pass to the next grade if they told anyone, he said. So they remained silent. Especially Thavery: she didn’t want to bring shame upon herself.

But her friend, also a victim, saw what happened and spoke up. She told Thavery’s father.

Soon, Chhen’s web of abuse began to unravel.

A systemic problem

Like many other child victims in Cambodia, Thavery has been failed by the judicial system and the authorities tasked with protecting her.

Her case follows a pattern of institutionalised abuse against children, where victims are threatened and shamed and powerful perpetrators secure silence. If caught, they are often quietly moved to other classrooms or other positions within the Ministry of Education.

Last December in Svay Rieng, teacher Duong Sinet was investigated for allegedly forcing an 11-year-old girl to strip in front of the class. Her case was not investigated until three months later. The girl had stopped attending school. The teacher was first moved to another class, then into a desk job. He spent six months in pre-trial detention, only to return to a job in an Education Ministry office afterward.

Around the same time, a primary school teacher in Battambang province took two young girls to a cassava field, stripped them, kissed them, and inserted his fingers into them. He was sentenced and jailed.

At least four foreign teachers were arrested on child abuse charges last year. Some were employed despite histories of child abuse, prompting calls for stricter screenings.

The Ministry of Education did take some action in September of this year, releasing its first policy to protect schoolchildren from abuse, developed in cooperation with children’s rights organisations including UNICEF and Plan International.

The policy aims to keep records of offending teachers so they are not re-hired, guarantee that teachers who commit a crime are punished by law, establish a reporting mechanism for children, and eliminate discrimination against child victims. But it came too late for Thavery.

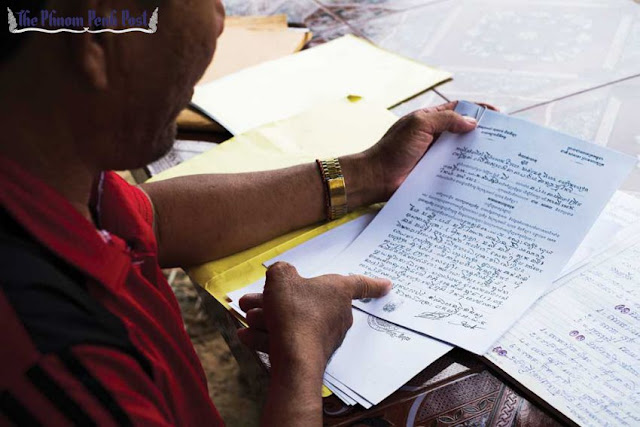

Despite the efforts of her uncle, Khiev Khuy, and other victims’ relatives, justice seems out of reach.

Elusive justice

The case brought by Thavery and three others has now seen Chhen, the alleged perpetrator, charged by the Kampong Chhnang Provincial Court. A warrant for his arrest was issued early last month. But he remains free, working in an administrative role in the primary school bureau of the provincial department of education.

Altogether, the stop-start case has spanned more than three years. The alleged abuse began in January 2013, with the first girls coming forward in May. But in July, court prosecutor Penh Vibol suspended the case after determining an “absence of crime”.

When assessing the complaints lodged by the parents, the prosecutor wrote: “It is not the parents who witnessed this with their own eyes. Only their children told them.”

The allegations of indecent assault, which carries a one- to three-year jail sentence, were unclear, he said. “The action of the complainants is just to assign blame . . . to slander the teacher’s reputation”, the decision reads.

When a staffer from human rights organisation Adhoc publicly criticised the decision, Vibol issued a court summons for him.

Vibol now serves as the deputy director general of the department of prosecutions and criminal affairs at the Ministry of Justice.

The girls’ case was resurrected in 2015, and has continued with a rotating door of prosecutors and judges. Last October, the investigating judge informed the Ministry of Education of the charges against Chhen. They have yet to offer a response.

In March, the victims’ families appealed to the Ministry of Justice to intervene. In August, the ministry wrote to the court demanding to know the status of the case. Finally, the court issued the arrest warrant. Chhen’s alleged threats and the doubt of children’s testimony have so far protected the teacher.

But so, too, have the authorities. Pich Sambo, the director of the Kampong Chhnang education department, unreservedly defends him, saying he is a “good teacher” that the community “supported 100 percent”.

This week, the Ministry of Justice, the Ministry of Education and the Kampong Chhnang police were unable to give credible answers as to why Chhen remains free.

“When the judge issued a warrant to bring him in, we came to look for him at his residence and we could not find him,” Kampong Chhnang provincial police deputy chief Pol Vuthy says.

Education spokesman Ros Salin, who has called out “immoral” teachers in the past, says only that the department is “working on the aspects of his misconduct” and “taking care of that”.

Shielded from scrutiny

Thavery’s old school is deserted on a Friday afternoon. All of the doors are fastened shut with a padlock. The mustard yellow walls are the only source of colour on the grounds, where strangler fig trees thrive.

Chhen hid his abuse behind these walls. His classroom threats had worked before. After the four girls’ sexual assault allegations came to light, several students in Chhen’s 2012 class came forward with their own accounts, village chief Som Bun Chhoeun says.

Teachers at the school say they had no idea what was going on. One, Ouk Sek, says Chhen worked at the school for about three years before the allegations, and though she had seen him “playing” with female students by touching their backs, she did not suspect dark intent.

“When the incident happened, I was very shocked. I was sweating like a pig and shaking. I had no idea,” Sek says.

Chhen’s status as a teacher gave him credibility before the court that was not afforded to his victims.

Court documents show that 14 classmates thumbprinted a document testifying to the truth of the allegations, says village chief Som Bun Chhoeun.

“But when they were in court, they did not dare to talk, because they were scared,” he says.

Research conducted by Hagar International last year found that for children, such intimidation is common in Cambodia. Of the 54 victims surveyed, almost all of them say they were afraid in the courtroom, with some forced to come face-to-face with their abusers.

Hagar chief executive Micaela Cronin says that children can be reliable witnesses, but the impact of prolonged cases is profound. Victims want to see justice and move on. But as long as a perpetrator is at large, it is difficult to regain a sense of safety in the community, she explains.

Cronin adds that while recognition of the specific needs of children is growing, including the recently adopted Juvenile Justice Law, “Cambodia’s legal system is still not effective for all child victims”, especially when it comes to social services.

Aimyleen Gabriel, World Vision’s technical leader for child protection, agrees that support is “severely lacking”. “There are no social workers at the commune level who can provide the necessary support to victims of physical or sexual violence,” she says.

Furthermore, many cases aren’t settled in court at all. World Vision data show that over half of cases are settled informally with compensation. “Victims [and their families] often do not go further in prosecuting the perpetrator due to perceived or real barriers,” Gabriel says.

Unfortunately, teachers are common abusers. According to a 2014 study on violence against children in Cambodia, which surveyed more than 2,500 children, teachers were one of the most cited perpetrators of physical violence against children outside the home.

For more than a quarter of teenage girls who had experienced sexual abuse, their first assault occurred on school grounds.

But schools are also regularly cited as safe places, where children enjoy spending time, says Iman Morooka, a spokesperson for UNICEF Cambodia.

She points out that there is no operative child protection system in Cambodian schools. “That’s why it’s vital to ensure that schools are safe places free from violence for children and to establish confidential reporting systems in schools,” she says.

Shame and silence

About a month after the complaints were filed, Chhen was moved to his desk job. So it wasn’t his continued presence at school that forced Thavery to drop out, but the noxious shame.

“It is my fault,” Thavery says, eyes downcast, though she can’t quite articulate why.

Gabriel, of World Vision, notes that when it comes to sexual abuse, “it is still common to direct some blame towards girls, noting the way they dress, or that they seduced the perpetrator, as a reason for the abuse”.

But Khuy, Thavery’s uncle, lays the blame elsewhere.

“The big mistake was made by the teacher and secondly, by the court,” he says.

“If they had taken action early, the children could still go to school and their future would not be destroyed.”

Thuy has been relentless in fighting for his niece; he is representing her because her mother died of uterine cancer when she was young, and her father is not well-educated.

Wiping his tears, he says a fair, expeditious trial would have vindicated Thavery. “Society should bring her up and encourage her, not look down on her,” he adds.

Only one of the girls who allegedly faced abuse remains in school.

Her father, Sopheap*, takes a break from fixing a truck and says he is proud of his daughter for staying in the classroom.

“I told my daughter to close her ears and close her eyes to whatever they say, and just continue her studies,” he says.

Wiping thick black grease from his hands, Sopheap says the repeated suspensions of the children’s case in court left him without much faith in the system.

“I feel hopeless in my heart,” he says.

Thavery, like Sopheap’s daughter, was a bright student – one of the top in her class. She still has curious eyes, though they are clouded by what her uncle calls a “broken spirit”.

Before, she wanted to be a doctor, to help people like her mother. Now, after the alleged abuse, Thavery says she wants to be a lawyer.

“I do not want people to look down on me,” she says, quietly defiant.

“I want justice.”

*Names have been changed to protect identities.

From KI Media - Khmer Intelligence

via_IFTTT

0 Comments